In this section, we are concerned with television talent and the major ways of behaving in front of the camera, doing makeup, and selecting what to wear. The material is divided into four sections:

1. Performing techniques, including the performer's relationship to the camera, to audio, and to timing, and the ways he or she receives cues and prompting.

2. Acting techniques, which differ markedly from stage and motion picture acting methods.

3. Makeup, in respect to improving the talent's appearance. Corrective and character makeup are not discussed because they are seldom required in small station operation.

4. Clothing and costuming, containing some of the basic principles of how dress should be adjusted to the requirements of the camera. No attempt has been made to include aesthetic criteria for what to wear, since they-like color harmony, for example--are discussed extensively in related literature.

The people who appear on the television screen have varied communication objectives: some seek to entertain, educate, inform; others, to persuade, convince, sell. Nevertheless, the main goal of each of them is to communicate with the television audience as effectively as possible.

We can arbitrarily divide all television talent (which stands, not always too accurately, for all people performing in front of the television camera) into two large groups: (1) performers and (2) actors. The difference between them is fairly clear-cut. The television performer is engaged basically in non-dramatic activities. Performers play themselves and do not assume roles of other characters; they sell their own personalities to the audience. The television actor or actress, on the other hand, always portrays someone else; he or she projects a character's personality rather than his or her own.

=================

Actor, or Actress--A person who appears on camera in dramatic roles. The actor or actress always portrays someone else.

Blocking--Carefully worked out movement and actions by the talent, and movement of all mobile television equipment.

Clothing --Regular clothes worn on camera, in contrast to a costume.

Costume-- Special clothes worn by an actor or actress to depict a certain character or period; in contrast to clothing, the regular clothes worn by a performer.

Cue Card --Also called idiot sheet. A hand-lettered card that contains copy, usually held next to the camera lens by floor personnel.

Pancake --A makeup base, or foundation makeup, usually water-soluble and applied with a small sponge.

Pan Stick --A foundation makeup with a grease base. Used to cover a beard shadow or prominent skin blemish.

Performer-- A person who appears on camera in non-dramatic shows. The performer plays himself or herself, and does not assume someone else's character.

Speed Up --A cue to the talent to speed up whatever he or she is doing.

Stretch --A cue to the talent to slow down whatever he or she is doing.

Taking Lens-- Also called on-the-air lens. Refers to the lens on turret cameras that is actually relaying the scene to the camera pickup tube.

Talent --Collective name for all performers and actors who appear regularly on television.

Teleprompter A mechanical prompting device that projects the moving copy over the lens, so that it can be read by the talent without losing eye contact with the viewer.

Wind Up --A cue to the talent to finish up whatever he or she is doing.

=================

Performing Techniques:

The television performer speaks directly to the camera or communicates with other performers or the studio audience, fully aware of the presence of the television audience. His or her audience is not a mass audience but only a small, intimate group that has gathered in front of a television set. If you think of yourself as a performer, it may help you to imagine your audience as being a family of three, seated in their favorite room, about ten feet away from you.

The definition of the television audience as usually expressed by modern sociologists is thus drastically changed for the television performer.

The large, anonymous, and heterogeneous mass becomes a small group of people, a family seated in a favorite room, watching television. With this picture in mind, there is no reason for the per-former to scream at the "millions of people out there in video land"; rather, the more successful approach is to talk quietly and intimately to the family who were kind enough to let you come into their home.

When you assume the role of a television performer, the camera becomes your audience. You must adapt your performance techniques to its characteristics and to other important production elements, such as audio and timing. In this section we will, therefore, discuss (1) the performer and the camera, (2) the performer and audio, (3) the performer and timing, (4) the floor manager's cues, and (5) prompting devices.

Performer and Camera:

The camera is not a piece of dead machinery; it sees everything you do or do not do. It sees how you look, move, sit, and stand-in short, how you behave in a variety of situations. At times it will look at you much more closely and with greater scrutiny than a polite person would ever dare to do. It will reveal the nervous twitch of your mouth when you are ill at ease and the expression of mild panic when you have forgotten a line. The camera will not look politely away because you are scratching your ear. It will faithfully reflect your behavior in all pleasant and unpleasant details. As a television performer, therefore, you must carefully control your actions without ever letting the audience know that you are conscious of doing so.

Camera Lens:

Since the camera represents your audience, you must look directly into the lens whenever you intend to establish eye contact with your viewer. As a matter of fact, you will discover that you must stare into the lens and keep eye contact much more than you would with an actual person. The reason for this seemingly unnatural way of looking is that, when you appear on a closeup shot, the concentrated light and space of the television screen highly intensifies your actions. Even if you glance away from the lens ever so slightly, you break the intensity of the communication between you and the viewer; you break, though temporarily, television's magic. Try to look into the lens as much as you can, but in as casual and relaxed a way as possible.

If you work with a turret camera, make sure that you look into the "taking," or on-the-air, lens, whose location differs with almost every turret camera. Ask the floor manager or the camera operator which lens you should look at.

Camera Switching If two or more cameras are used, you must know which one is on the air so that you can remain in direct contact with the audience. When the director changes cameras, you must follow the floor manager's cue (or the change of tally lights) quickly but smoothly.

Don't jerk your head from one camera to the other. If you suddenly discover that you have been talking to the wrong one, look down as if to collect your thoughts and then casually glance into the "hot" camera and continue talking in that direction until you are again cued to the other camera. This method works especially well if you work from notes. You can always pretend to be looking at your notes, while, in reality, you are changing your view from the "wrong" to the "right" camera.

In general, it is useful to ask your director or floor manager if there will be many camera changes during the program, and approximately when the changes are going to happen. If the show is scripted, mark all camera changes in your script.

If the director has one camera on you in a medium shot (MS) or a long shot (LS), and the other camera in a closeup (CU) of the object you are demonstrating, it is best to keep looking at the long-shot camera during the whole demonstration, even when the director switches to the closeup camera. This way you will never be caught looking the wrong way, since only the long shot camera is focused on you.

Closeup Techniques:

The tighter the shot, the harder it is for the camera to follow fast movement. If a camera is on a closeup, you should restrict your motions severely and move with great care. Ask the director whether he plans closeups and approximately when. In a song, for example, he may want to shoot very closely to intensify an especially tender and intimate passage. Try to stand as still as possible; don't wiggle your head. The closeup itself is intensification enough. All you have to do is sing well.

When demonstrating small objects on a closeup, hold them steady. If they are arranged on a table, don't pick them up. You can either point to them or tilt them up a little to give the camera a better view. There is nothing more frustrating for camera operator and director than a performer who snatches the product off the table just when the camera has a good closeup of it. A quick look in the studio monitor will usually tell you how you should hold the object for maximum visibility on the screen. If two cameras are used, "cheat" (orient) the object somewhat toward the closeup camera. But don't turn it so much that it looks unnaturally distorted on the wide-shot camera.

Warning Cues:

In most non-dramatic shows--lectures, demonstrations, interviews--there is generally not enough time to work out a detailed blocking scheme. The director will usually just walk you through some of the most important crossovers from one performing area to the other, and through a few major actions, such as especially complicated demonstrations. During the on-the-air performance, therefore, you must give the director and the studio crew visual and audible warning of your unrehearsed actions. When you want to get up, for instance, shift your weight first, and get your legs and arms into the right position before you actually stand up. This will give the camera operator as well as the microphone boom operator enough time to prepare for your move. If you pop up unexpectedly, however, the camera may stay in one position, focusing on the middle part of your body, and your head may hit the microphone, which the boom operator, not anticipating your sudden move, has solidly locked into position.

If you intend to move from one set area to another, you may use audio cues. For instance, you can warn the production crew by saying: "Let's go over to the children and ask them . . . " or, "If you will follow me over to the lab area, you can actually see . . . . " Such cues will sound quite natural to the home viewer, who is generally unaware of the number of fast reactions these seemingly unimportant remarks may trigger inside the television studio. You must be specific when you cue unrehearsed visual material. For example, you can alert the director of the upcoming slides by saying: "The first picture (or even slide) shows. . . ." This cuing device should not be used too often, however. If you can alert the director more subtly yet equally directly, do so.

Don't try to convey the obvious. It is the director who runs the show, and the talent is not the director. An alert director does not have to be told by the performer to bring the cameras a little closer to get a better view of the small object. This is especially annoying if he or she has already obtained a good closeup through a zoom-in. Also, avoid walking toward the camera to demonstrate an object. Through the zoom lens, the camera can get to you much faster than you to the camera.

Also you may walk so close to the camera that the zoom lens can no longer keep focus.

Performer and Audio:

As a television performer, you must not only look natural and relaxed but you must also be able to speak clearly and effectively; it rarely comes as a natural gift. Don't be misled into believing that a super bass and affected pronunciation are the two prime requisites for a good announcer. On the contrary: first, you need to have something important to say; second, you need to say it with conviction and sincerity; third, you must speak clearly so that everybody can understand you.

Nevertheless, a thorough training in television announcing is an important prerequisite for any performer.

[[ Stuart W. Hyde, Television and Radio Announcing, 2nd ed. (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Co., 1971). ]]

Microphone Techniques:

In Section 7 we have already discussed the most basic microphone techniques. Here is just a short summary of the main points about the performer's handling of microphones or assisting the microphone operator.

Most often you will work with a lavaliere microphone. Once it is properly fastened, you don't have to worry about it anymore. If you have to move from one set area to another on camera, make sure that the mike cord does not get tangled up in the set or set props. Gently pull the cable behind you to keep the tension off the mike itself.

When using a hand microphone, make sure that you have enough cable for your planned actions.

Treat it gently. Speak across it, not into it. If you are interviewing somebody in noisy surroundings, such as in a downtown street, hold the microphone near you when you are doing the talking, and then point it toward the person as he responds to your questions.

When working with a boom microphone, be aware of the boom movements without letting the audience know. Give the boom operator enough warning so that he or she can anticipate your movements. Slow down somewhat, so that the boom can follow. Especially don't make fast turns, for they involve a great amount of boom movement. If you have to turn fast, try not to speak. Don't walk too close toward the boom; the operator may not be able to retract it enough to keep you "on mike" (within good microphone pickup range). Try not to move a desk mike once it has been placed by the audio engineer. Sometimes the microphone may be pointing away from you toward another performer, but this may have been done purposely to achieve better audio balance.

Audio Level

A good audio engineer will take your audio level before you go on the air. Many performers have the bad habit of mumbling or speaking softly while the level is being taken, and then, when they go on the air, blasting their opening remarks. If a level is taken, speak as loudly as though you are actually going into your opening remarks. Thus the audio engineer will know where to turn the pot for an optimum level.

Opening Cue

At the beginning of a show, all microphones are dead until the director gives the cue for studio audio. You must, therefore, wait until you receive the opening cue from the floor manager. If you speak beforehand, you will not be heard. Don't take your opening cue from the red tally lights on the cameras unless you are instructed to.

Performer and Timing

Television operates on split-second timing. Although the director is ultimately responsible for getting the show on and off on time, the performer has a great deal to do with successful timing.

Aside from careful pacing throughout the show, you must learn how much program material you can cover after you have received a three-minute, a two-minute, a one-minute, and a thirty-second cue. You must, for example, still look comfortable and relaxed although you may have to cram a great amount of important program material into the last minute. On the other hand, you must be prepared to fill an extra thirty seconds without appearing to be grasping for words and things to do. This kind of presence of mind, of course, needs practice and cannot be learned solely from a television handbook.

Floor Manager's Cues

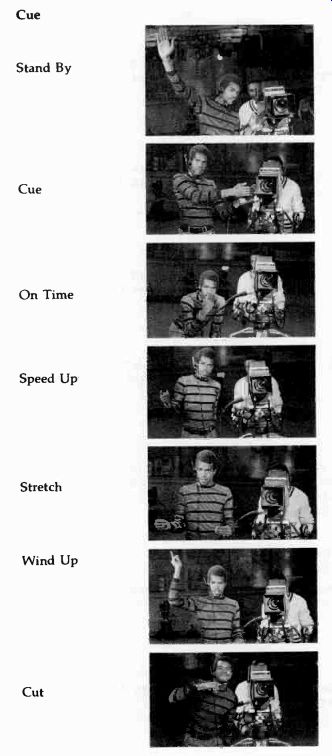

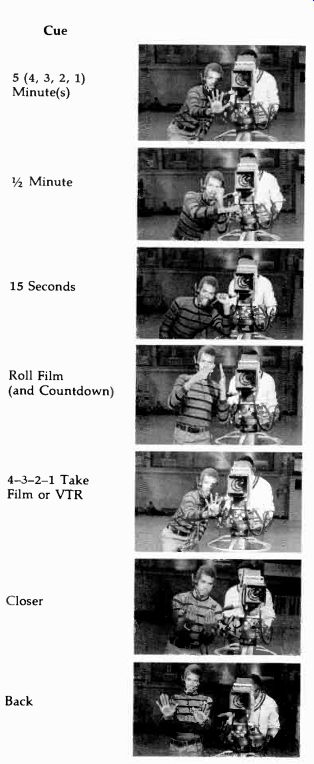

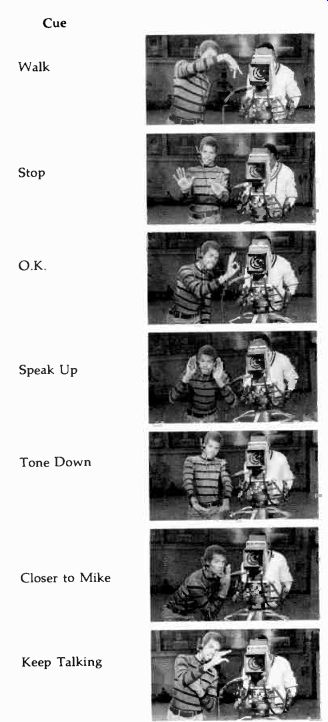

The floor manager, who is the link between the director and you, the performer, can communicate with you nonverbally even while you are on the air. He can tell you whether you are too slow or too fast in your delivery, how much time you have left, whether or not you speak loudly enough or hold an object correctly for the closeup camera. We can group these visual cues into three types: (1) time cues, (2) directional cues, and (3) audio cues. Although stations use slightly different cuing signals and procedures, they still will fall into one of the above categories. If you are working with an unfamiliar production crew, ask the floor manager to go over his cues before you go on the air.

------------------------

13.1 Floor Manager's Cues.

Cue Meaning Hand Signal

Stand By Cue On Time Speed Up Stretch Wind Up Cut Show about to start.

Show goes on the air.

Go ahead as planned.

(On the nose.) Accelerate what you are doing. You are going too slowly.

Slow down. Too much time left. Fill until emergency is over.

Finish up what you are doing. Come to an end.

Stop speech or action immediately.

Extends arm above his head and points with other hand to camera that will go on the air.

Points to performer or live camera.

Touches nose with forefinger.

Rotates hand clockwise with extended forefinger. Urgency of speedup is indicated by fast or slow rotation.

Stretches imaginary rubber band between his hands.

Similar motion as speed up, but usually with extended arm above head.

Sometimes expressed with raised fist, or with a good-bye wave, or by hands rolling over each other as if wrapping an imaginary package.

Pulls index finger in knifelike motion across throat.

5 (4, 3, 2, 1)

Minute(s)

1 Minute 15 Seconds Roll Film (and Countdown)

4-3-2-1

Take Film or VTR Closer Back 5 (4, 3, 2, 1) minute(s) left until end of show.

30 seconds left in show.

Holds up five (four, three, two, one) finger(s) or small card with number painted on it.

Forms a cross with two index fingers or extended hands. Or holds card with number.

15 seconds left in Shows fist (which can also mean wind show. up). Or holds card with number.

Projector is rolling.

Film is coming up.

Academy numbers as they flash by on the preview monitor, or VTR beeper countdown.

Holds extended left hand in front of face, moves right hand in cranking motion.

Extends four, three, two, one fingers; clenches fist or gives cut signal.

Directional Cues Performer must come closer or bring object closer to camera.

Performer must step back or move object away from camera.

Moves both hands toward himself, palms in.

Uses both hands in pushing motion, palms out.

Walk Stop O.K. Speak Up Tone Down Closer to Mike Keep Talking Performer must move Makes a walking motion with index and to next performing middle fingers in direction of movement area.

Stop right here. Do Extends both hands in front of him, not move any more. palms out.

Very well done. Stay right there. Do what you are doing.

Forms an "O" with thumb and forefinger, other fingers extended, motioning toward talent.

Audio Cues

Performer is talking too softly for present conditions.

Performer is too loud or too enthusiastic for the occasion.

Performer is too far away from mike for good audio pickup.

Keep on talking until further cues.

Cups both hands behind his ears, or moves right hand upwards, palm up.

Moves both hands toward studio floor, palms down, or puts extended forefinger over mouth in shhh-like motion.

Moves right hand toward his face.

Extends thumb and forefinger horizontally, moving them like the beak of a bird.

------------------------

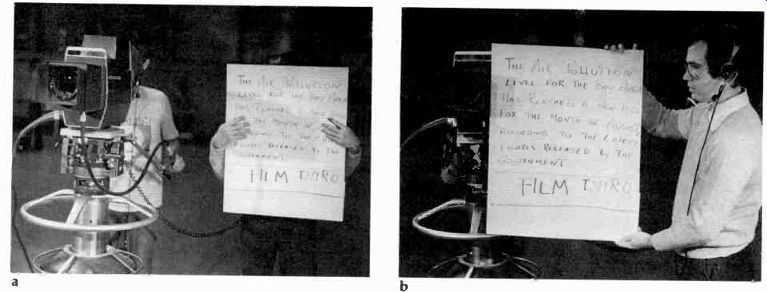

13.2 (a) This is the wrong way to hold a cue card. First, the card is too far

away from the lens, forcing the talent to lose eye contact with the viewer

(the lens). Second, his hands cover up important parts of the copy. Third,

he cannot follow the lines as read by the talent. He will not be able to change

cards for smooth reading. (b) This is the correct way of holding a cue card.

The card is as close to the lens as possible, the hands do not cover the copy,

and the floor manager reads along with the talent, thereby facilitating smooth

card changes.

React to all cues immediately, even if you think one of them is not appropriate at that particular time. Your director would not give the cue if it were not absolutely necessary. A truly professional performer is not one who never needs any cues and can run the show all by himself; he is the one who can react to all signals quickly and smoothly.

Don't look nervously for the floor manager if you think you should have received a cue; he will find you and draw your attention to his signal.

When you receive a cue, don't acknowledge it in any way. The floor manager will know whether you have noticed it or not.

The table of cues (13.1) indicates the standard time cues, directional cues, and audio cues that are used by most television stations with only minor, if any, variations.

Prompting Devices:

In addition to direct cues, television prompting devices are of great help to the performer who fears suddenly forgetting his lines or who has had no time to memorize a difficult copy that may have been handed to him just before the performance. The sensitive studio microphones make most audible prompting impossible. Since earphones and hearing-aid methods have not proved very successful, most television line prompters depend upon sight.

[[2 . As a trademark, it is spelled TelePrompTer. ]]

The visual prompting device must be designed so that the television viewer is not aware of it, and the performer must be able to read the prompting sheet without appearing to lose eye contact with the viewer. The equipment must be reliable, so that the performer can deliver his lines uninterrupted by mechanical failure. Two major prompting devices have proved highly successful: (1) cue cards, or idiot sheets, and (2) the teleprompter. 2

Cue Cards:

Cue cards or, as they are often called, idiot sheets are generally held by a member of the production crew as close to the lens of the on-the-air camera as possible (see 13.2). There are many types, and the choice depends largely on what the performer is used to and what he likes to work with. Usually they consist of large cardboard sheets on which the copy is hand-lettered with a large felt pen. The size of the cards and the lettering depends on how well the individual can see and how far the camera is away from him.

In using the cue cards, you must learn to glance at the copy without losing eye contact with the lens for more than a moment. Make sure the floor manager has the cards in the right order. If the cue sheet operator forgets to change them, snap your fingers to attract his or her attention; in an emergency you may have to ad-lib until the system is functioning again. Hopefully, you will have studied the copy sufficiently so that your ad-lib makes sense.

Teleprompter:

The most advanced and frequently used prompting device is the teleprompter, a device that pulls a long sheet of paper with the copy on it from one roller to another at a speed adjustable to your reading pace. The lettering is magnified and projected onto a glass plate placed directly in front of the camera lens.

Thus you can read the copy, which appears in front of the lens, and maintain eye contact with the viewer at the same time. The projected letters are invisible to the camera, since they are too close to the lens to come into focus. The roll of paper, on which copy is typed with an oversized typewriter, can hold continuous information for a full hour's newscast, for example. Most newscasters read their copy off the teleprompter, with the script serving as backup in case the mechanism should fail. (See 13.3.) There are some disadvantages to this otherwise highly useful prompting device: (1) The rental fee for the teleprompter is relatively high. (2) The camera with the teleprompter attachment is no longer flexible, since it must stay with the performer at all times. (3) If frequent cutting from camera to camera is intended (as happens in a newscast), teleprompters that run in sync or monitor must be placed either on all active cameras or on floor-stands.

Acting Techniques:

Contrary to the television performer, the television actor or actress always assumes someone else's character and personality.

To become a good television actor or actress, you must first of all learn the art of acting, a subject beyond the objective of this section. This discussion will merely point out how you must adapt your acting to the peculiarities of the television medium.

Many excellent actors consider television the most difficult medium in which to work. The actor always works within a studio full of confusing and impersonal technical gear; and yet he must appear on the screen as natural and lifelike as possible.

Many times the "television" actor also works in motion pictures. The production techniques and the equipment used in film for television are identical to those of film for motion picture theaters, but film making for television is considerably faster. Film shot for the television screen, in contrast to the large motion picture screen, requires acting techniques more closely related to live or videotaped television.

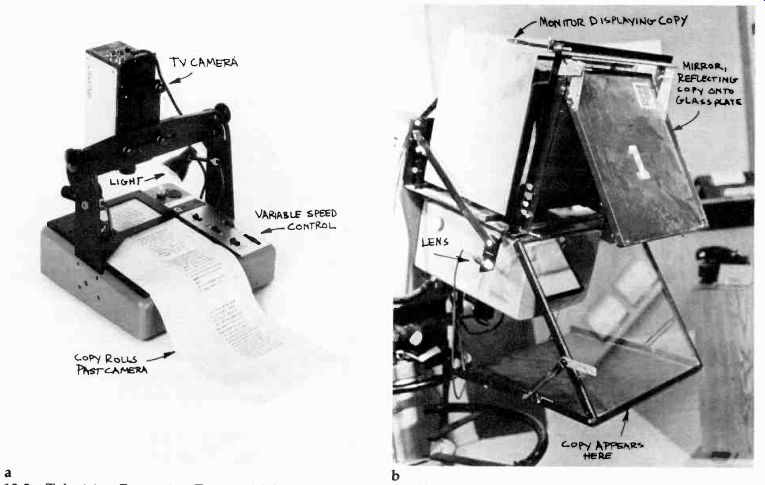

13.3 Television Prompting Device: (a) The copy, typed on a news typewriter

with oversized letters, is placed in a special variable-speed crawl. A simple

vidicon camera picks up the copy and relays it to a monitor, or monitors,

mounted on one or all the active cameras. (b) The monitor that displays the

copy is mounted on the camera. A mirror projects the copy as it appears on

the monitor screen onto a glass plate directly over the lens. (c) You can

then read the copy without losing eye contact with the lens (the viewer).

The advantage of this system is that a single copy can be displayed on two

or more cameras.

It is difficult to establish rigid principles of television acting techniques that are applicable in every situation. The particular role and even the director may require quite different forms of expression and technique from the actor or actress.

The television medium, however, dictates some basic behavior patterns that the actor must accept if he wants to make it work for him instead of against him. Let's look briefly at some of these requirements, among them (1) audience, (2) actions, (3) blocking, (4) speech, (5) memorizing lines, (6) timing, and (7) director-actor relationship.

Audience:

When you act on television, you have no rapport with the audience-people you can see, or at least feel, and who applaud and elevate you to your best possible performance. In television, you are acting before constantly moving cameras that represent your assumed audience. Like the television performer, you must be camera-conscious, but you should never reveal your knowledge of the cameras' presence. The viewer (now the camera) does not remain in one position, as he would in the theater; he moves around you, looks at you at close range and from a distance, from below and from above; he may look at your eyes, your feet, your hands, your back, whatever the director selects for him to see. And at all times you must look completely convincing and natural; the character you are portraying must appear on the screen as a real, living, breathing human being.

Keep in mind that you are playing to a camera lens and not to an audience; you need not (and should not) project your motions and emotions as you would when acting on stage. The television camera does the projecting-the communicating--for you. Internalization, as opposed to externalization, of your role is a key factor of your performance. You must attempt to become as much as possible the person you are portraying, rather than to act him out. Thus, your reactions are equally as effective on television as your actions.

Actions The television camera is restrictive in many ways.

It looks at the set and at you mostly in closeups.

This means that your physical actions must be confined to the particular area the camera chooses to select, often unnaturally close to the other actors.

The television closeup also limits the extent of your gestures, concentrating on more intimate ways of emotional expression. A closeup of a clenched fist or a raised eyebrow may reflect your inner feelings and emotions more vividly than the broad movements necessary for the theater.

Blocking:

You must be extremely exact in following rehearsed blocking. Sometimes mere inches become important, especially if the cameras are set up for special effects. The director may, for instance, want to use your arm as a frame for the background scene or position you for a complicated over-the-shoulder shot. The precise television lighting and the limited microphone radius (especially in small station production) are also factors that force you to adhere strictly to the initial blocking.

Once the show is on the air, you have an obligation to follow the rehearsed action carefully.

This is not the time to innovate just because you have a sudden inspiration. If the director has not been warned of your change, the new blocking will always be worse than the previously rehearsed one. The camera has a limited field of view; if you want to be seen, you must stay within it.

Sometimes the director will place you in a position that looks entirely wrong to you, especially if you consider it in relation to the other actors.

Don't try to correct this position on your own by arbitrarily moving away from the designated spot. A certain camera position and a special lens position may very well warrant unusual blocking to achieve a special effect.

The television cameras quite frequently photograph your stage business in a closeup. This means that you must remember all the rehearsed business details and execute them in exactly the same spot in which they were initially staged.

Speech:

Compared to radio, the television boom microphone is generally a good distance away from you. You must, therefore, speak clearly. But speak naturally; projecting your voice in the theater tradition sounds very artificial on television.

Memorizing Lines:

As a television actor or actress, you must be able to learn your lines quickly and accurately. If, as is the case in the soap operas, you have only one evening to learn a half-hour's role for the next day, you must indeed be a "quick study." And don't be misled into thinking that you can ad-lib during such performances, since you have "lived" the role for so long. Most of your lines are important not only from a dramatic point of view but also because they serve as video and audio cues for the whole production crew.

Even for a highly demanding role, you may have only a few weeks to prepare. As a television actor, you should not rely on prompting devices; after all, you should live, not read, your role.

Timing:

Just like the performer, the actor in television must have an acute sense of timing. Timing matters for pacing your performance, for building to a climax, for delivering a punch line, and also for staying within a tightly prescribed clock time.

Even if you are videotaping a play scene by scene, you still need to observe carefully the stipulated running times for each take. You may have to stretch out a fast scene without making the scene appear to drag, or you may have to gain ten seconds by speeding up a slow scene without destroying its solemn character. You must be flexible without stepping out of character.

Always respond immediately to the floor manager's cues. Don't stop in the middle of a scene simply because you disagreed with one.

Play the scene to the end and then complain. Minor timing errors can often be corrected later during the editing process.

Director-Actor Relationship:

As a television actor, you cannot afford to be temperamental. There are too many people who have to be coordinated by the director. Although the actor is important to the television show, so are other people-the floor crew, the engineer at the transmitter, the boom operator, and the video engineer.

Even though you may find little opportunity for acting in small station operation, make an effort to learn as much about it as possible. An able actor is generally an effective television performer; a television director with acting training will find himself in good stead in most of his directing assignments.

Makeup:

All makeup is used for three basic reasons: (1) to improve appearance, (2) to correct appearance, and (3) to change appearance.

Standard street makeup is used daily by many women to accentuate and improve their features.

Minor skin blemishes are covered up, and the eyes and lips are emphasized.

Makeup can also be used to correct closely or widely spaced eyes, sagging flesh under the chin, a short or long nose, a slightly too prominent forehead, and many similar minor faults.

If a person is to portray a specific character in a play, a complete change of appearance may be necessary. Drastic changes of age, race, and character can be accomplished through the creative use of makeup techniques.

The different purposes for applying cosmetics require, of course, different techniques. Improving someone's appearance calls for the least complicated procedure; to correct someone's appearance is slightly more complicated; and changing an actor's appearance may require involved and complex methods.

Most shows in small station operation require only makeup that improves the appearance of a performer. More complicated makeup work, such as making a young actress look eighty years old, is left to the professional makeup artist. Therefore, there is no need for you to burden yourself with learning all about corrective and character makeup techniques. All we will do is to give you some idea about television makeup in respect to its basic (1) technical requirements, (2) materials, and (3) techniques.

Technical Requirements:

Like so many other production elements, makeup, too, must yield to some of the demands of the television camera. These are (1) color distortion, (2) color balance, and (3) closeups.

Color Distortion:

As we pointed out repeatedly through the preceding sections, the skin tones are the only color references the viewer has for the correct adjustment of colors on his home receiver.

Their accurate rendering is, therefore, of the utmost importance. Makeup plays a major role in this endeavor.

Generally, cool colors (hues with a blue tint) have a tendency to overemphasize their bluishness, especially in high color-temperature lighting. Also, cool reds turn dark on the monochrome set. Warm colors (warm reds, oranges, browns, and tans) are therefore preferred for television makeup. They usually provide more sparkle, especially when used on a dark-skinned face.

The basic foundation color should match the natural skin tones as closely as possible, regardless of whether the face is light (Caucasian or Oriental) or dark (Chicano or Black). However, since the camera might emphasize dense shadow areas with a bluish or purple tint, especially on dark skin, warm rather than cool foundation colors are preferred. Be careful, however, that the skin color does not turn pink. As much as you should guard against too much blue in a dark face, you must watch for too much pink in a light face.

The natural reflectance of a dark face (especially of very dark-skinned Blacks) often produces unflattering highlights. These should be toned down by a proper pancake or a translucent powder; otherwise, the video engineer will have to compensate for the highlights through shading, rendering the dark picture areas unnaturally dense.

Color Balance:

Generally, it is a good plan for the art director, scene designer, makeup artist, and costume designer to coordinate all the colors in production meetings. In small station operations, there should be little problem with such coordination since these functions may all be combined in one or two persons. At least you should be aware of this coordination principle and apply it whenever possible. Although the colors can be adjusted by the video control operator, the adjustment of one hue often influences the others. A certain balancing of the colors beforehand will make the technical "painting" job considerably easier.

In color television, the surrounding colors are sometimes reflected in the face and greatly exaggerated by the camera. Frequently, such reflections are inevitable, but you can keep them to a minimum by carefully watching the overall reflectance of the skin. It should have a normal sheen, neither too oily (high reflectance) nor too dull (low reflectance but no brilliance-the skin looks lifeless).

Closeups:

Television makeup must be smooth and subtle enough so that the performer's or actor's face looks natural even in an extreme closeup. This is directly opposed to theater makeup, where features and colors are greatly exaggerated for the benefit of the spectator in the last row. A good television makeup remains largely invisible, even on a closeup. Therefore, a closeup of a person's face under actual production lighting conditions is the best criterion for the necessity for and quality of makeup. If the performer or actor looks good on camera without makeup, none is needed. If the performer needs makeup and the closeup of his or her finished face looks normal, your makeup is acceptable. If it looks artificial, the makeup must be redone.

Materials:

Various manufacturers produce a great variety of excellent television makeup materials. Most makeup artists in the theater arts departments of a college or university have up-to-date lists readily available. In fact, most large drug stores can supply you with the basic materials for the average makeup for improving the performer's appearance.

While women performers are generally quite experienced in cosmetic materials and techniques, men performers may, at least initially, need some advice.

The most basic makeup item is a foundation that covers minor skin blemishes and cuts down light reflections from an overly oily skin. The water-base cake makeup foundations are preferred over the more cumbersome grease-base foundations.

The Max Factor:

CTV-1W through CTV-12W pancake series is probably all you need for most makeup jobs. It ranges from a warm light ivory color to a very dark tone for Blacks and other dark-skinned performers.

Women can use their own lipsticks or lip rouge, as long as the reds do not contain too much blue.

For Black performers and actresses especially, a warm red, such as coral, is more effective than a darker red that contains a great amount of blue.

Other materials, such as eyebrow pencil, mascara, and eye shadow, are generally part of every woman performer's makeup kit. Special materials, such as hair pieces or even latex masks, are part of the professional makeup artist's inventory. They are of little use in the everyday small station operation.

Techniques

It is not always easy to persuade performers, especially men, to put on necessary makeup. You may do well to look at your guests on camera before deciding whether they need any. If they do, you must be tactful in suggesting its application. Try to appeal not to the performer's vanity but, rather, to his desire to contribute to a good performance. Explain the necessity for makeup in technical terms, such as color and light balance.

If you have a mirror available, seat the performer in front of it so that he or she can watch the entire makeup procedure. Adequate, even illumination is very important. If you have to work in the studio, have a small hand mirror ready.

Most women performers will be glad to apply the more complicated makeup themselves--lipstick and mascara, for instance. Also, most regular television talent will prefer to apply makeup themselves; they usually know what kind they need for a specific television show.

When using pancake base, simply apply it with a wet sponge evenly over the face and adjacent exposed skin areas. Make sure to get the base right up into the hairline, and have a towel ready to wipe off the excess. If closeups of hands are shown, you must also apply pancake base to them and the arms. This is especially important for men performers who demonstrate small objects on camera. If an uneven suntan is exposed (especially when women performers wear bareback dresses or different kinds of bathing suits) all bare skin areas must be covered with base makeup.

Baldheaded men need a generous amount of pancake foundation to tone down obvious light reflections and to cover up perspiration.

Be careful not to give your male performers a baby-face complexion. It is sometimes even desirable to have a little beard area show. Frequently, a slight covering up of the beard with a beard-stick is all that is needed. If additional makeup foundation is necessary, a pan stick foundation around the beard area should be applied first and set with some powder. For color shows, a very light application of a yellow or orange greasepaint counteracts the blue of a heavy beard quite satisfactorily.

Clothing and Costuming:

In small station operation you will be concerned mainly with clothing the performer rather than costuming the actor. The clothes of the performer should be attractive and stylish but not too conspicuous or showy. The television viewer expects the person to be well dressed but not to overwhelm him with flashy outfits. After all, he or she is a guest in the viewer's home, not a night club performer.

Clothing:

Naturally, the type of clothing worn by the performer depends largely on his or her personal taste. It also depends on the type of program or occasion and the particular setting.

There are, however, some types of clothing that look better on television than others. Since the television camera may look at you from a distance and at close range, the lines and overall color scheme of your clothes are just as important as their texture and details.

Line:

Television has a tendency to put a few extra pounds on the performer. Clothing cut to a slim silhouette helps to combat this problem. Slim dresses and rather tight-fitting suits look more attractive than heavy, horizontally striped material, and baggy dresses and suits. The overall silhouette of your clothing should look pleasing from a variety of angles, and slim but comfortable on you.

Color:The most important thing to remember about the colors you wear is that they harmonize with the set. If your set is lemon yellow, don't wear a lemon-yellow dress. Also, avoid wearing a chroma key blue, unless you want to become translucent during the chroma key matting; then even a blue tie may give you trouble.

Although you can wear black or a very dark color, or white or a very light color, as long as the material is not glossy and highly reflective, try to avoid wearing a combination of the two. Or, if the set is very dark, try not to appear in a starched white shirt in front of it. If the set is kept in extremely light colors, don't wear black. As desirable as a pleasant color contrast is, especially when considering compatibility with monochrome reception, extreme brightness variations offer difficulties. Stark-white, glossy clothes can turn exposed skin areas dark on the television screen, or distort the more subtle colors. Black performers should try not to wear highly reflecting white or light yellow clothes. If you wear a dark suit, reduce the brightness contrast by wearing a pastel-colored shirt. Pink, light green, tan, or gray all photograph well on color and monochrome television.

As always, if you are in doubt as to how well a certain color combination photographs, check it on camera under actual lighting conditions and in the set you are going to use.

Texture and Detail:

While line and color are especially important on long shots; texture and detail become important at close range. Textured material often looks better than plain, but don't use patterns that are too contrasting or too busy.

We have already talked about the moiré effect that is caused by closely spaced geometric patterns such as herringbone weaves. Also, stripes in your clothing may extend beyond the fabric and bleed through surrounding sets and objects, an effect similar to color banding. Extremely fine detail in a pattern will either look too busy or appear smudgy.

The way to make your clothing more interesting on camera is not by choosing a detailed cloth texture, but by adding decorative accessories, such as scarves and, especially, jewelry. Although the style of the jewelry depends, of course, on the taste of the performer, in general, she should limit herself to one or two distinctive pieces. The sparkle of rhinestones, which used to cause annoying glares on monochrome television, turns into an exciting visual accent on color television.

When wearing a tie, again try to avoid tight, highly contrasting patterns. And, elegant as a tie pin may look on camera, it often interferes with the lavaliere microphone.

If a man and a woman, who are scheduled to appear on a panel show or an interview, were to ask you now what to wear for the occasion, what would you tell them? Here is a possible answer. Both of them should wear something in which they feel comfortable, without looking wide and baggy. Both should stay away from blue, especially if chroma key matting is to be used behind them during the interview. The woman might wear a slim suit, pantsuit, or dress, all with plain colors. Avoid black-and-white combinations, such as a black skirt and a highly reflecting white blouse or shirt.

Also, avoid highly contrasting narrow stripes or checkered patterns. Wear as little jewelry as possible, unless you want to appear flashy. If possible, find out the color of the set background and try to avoid similar colors in your outfit.

The man might wear a slim suit, or slacks and plain coat. Wear a plain tie or one with a very subtle pattern. Don't wear a white shirt under a black or dark blue suit or coat. Avoid checkered or herringbone patterns.

Costumes:

For small station operation, you don't need costumes. If you do a play or a commercial that involves actors, you can always borrow the necessary articles from a local costume rental firm or from the theater arts department of your local high school, college, or university. The theater arts departments usually have a well-stocked costume room from which you can draw most standard period costumes and uniforms.

If you use stock costumes on television, make sure that they look convincing even in a tight closeup. Sometimes the general construction and, especially, the detail of theater accessories are too coarse for the television camera. The color and pattern restrictions for clothing also apply for costumes. The total color design, the overall balance of colors among scenery, costumes, and makeup, is important in some television plays, particularly in musicals and variety shows where long shots often reveal the total scene, including actors, dancers, scenery, and props.

Summary:

Television talent stands for all persons who perform in front of the television camera. They are classified in two large groups: (1) television performers and (2) television actors and actresses.

Television performers are basically engaged in non-dramatic shows, such as newscasts, interviews, music shows. They always portray themselves. Television actors and actresses always play someone else; they project someone else's character.

Because their communication purposes are different, the two kinds of talent use somewhat different techniques. Specific production factors for the performer include (1) the performer and the camera, (2) the performer and audio, (3) the performer and timing, (4) the floor manager's cues, and (5) prompting devices. The specific production factors for the actor or actress include (1) audience, (2) actions, (3) blocking, (4) speech, (5) memorizing lines, (6) timing, and (7) director-actor relationship.

Makeup, clothing, and costuming are important aspects of the talent's preparation for on-camera work.

All makeup is used for three basic reasons: (1) to improve appearance, (2) to correct appearance, and (3) to change appearance. The technical requirements of makeup demand consideration of (1) color distortion, (2) color balance, and (3) closeups.

Clothing is worn by the performer, costumes by the actor or actress. When clothing is selected for on-camera use, attention must be paid to its general line, color, texture, and detail. When costumes are used, they must be chosen with the same discernment. In addition, for the costumed show, it is important to achieve an overall color balance among the various pieces of costume and the scenery.