by Bridget Paolucci

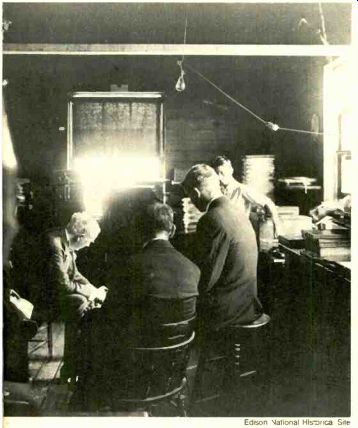

--------------- In the photograph at above, taken in the West Orange, New

Jersey, lab's music room in the early Twenties, Edison cups his hand behind

his ear the better to audition Helen Davis, who is giving her all to both

music and camera. The attentive pianist is her husband, Victor Young, who

is remembered today for his film scores.

Above, the inventor and his staff pass judgment on a prospective release

in the playback room, which was adjacent to the music room.

What was the inventor like as his own a&r man -- besides deaf? Some of his recording stars, still leading active lives, remember.

Rachmaninoff strode into the Edison recording studios and sat down at the piano. He was there to make a trial record. The inventor shuffled in close behind him. "Go ahead." said Edison. The massive hands moved over the keyboard in the grand Romantic style typical of Rachmaninoff. Edison interrupted: "Who told you you're a piano player? You're a pounder-that's what you are, a pounder!" Without a word, Rachmaninoff got up from the bench, put on his hat, and walked out.

WHEN Ernest Stevens now recalls the encounter in the early Twenties between Rachmaninoff and Edison, he wishes he had talked to the pianist be forehand. "I should have told him not to play any thing that would hurt the old gent's ears," he says.

[Bridget FL Paolucci is a writer, lecturer, and broadcaster whose specialty is music.]

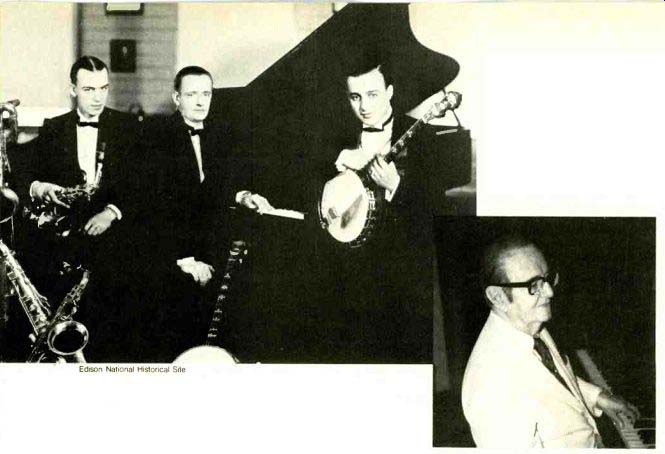

------- Edison National Historical: Another photo taken in the

music room of Edison's laboratory shows the Ernest L. Stevens trio about

to make an audition recording. Stevens, at center, is flanked by reedman

Archie Slater and banjoist Sam Brown. Today Stevens (below) still teaches

music in Montclair, New Jersey.

Stevens was Edison's personal pianist and arranger; it was his job to play the latest tunes for the inventor so he could decide what new music to record for release by the Edison Phonograph Works. Their collaboration began in 1918. Stevens was playing in an orchestra at the time, and a saxo phone player suggested that he contact his uncle at the Works about cutting a trial record. Edison heard the recording and hired Stevens. "He liked my playing because I was not a pounder," Stevens recalls. "I played my natural way, and my touch seemed to agree with his hearing." Edison always claimed that it takes a deaf man to hear. Although he was partially deaf, he could tune a piano and could judge orchestral balance and fidelity of tone with uncanny sureness. "He must have heard sounds no one else could hear," the soprano Elizabeth Lennox, one of his stars of the Twenties, explains. In her visits to his New York studio she never met Edison, whose head quarters was the Columbia Street laboratory in West Orange, New Jersey. But she describes his in fluence as "omnipresent. He always checked everything, and the recording studio personnel were always apprehensive about what he would say. He would reject wonderful records because he heard certain high sounds." Trumpet player Edna White, another of his stars of the Twenties, also felt Edison's authoritative presence. White was commissioned to record a virtuoso trumpet piece by Herbert Clark after Edi son had heard her audition recording and judged her tone "the loveliest trumpet sound I ever heard." When she arrived at the studio, conductor Cesare Sodero told her that they would rehearse something simple while trying to get a balance be tween the various sections of the orchestra. Each instrumentalist was seated on an individual plat form. For hours, soloist and orchestra played the Battle Hymn of the Republic while the platforms were pushed around in an effort to achieve the correct balance that was so crucial to winning Edison's approval. After lunch, Sodero announced that the seating arrangement was finally satisfactory and that they could begin cutting the first master. (All recording artists were required to produce three masters with the understanding that Edison would select the best of the three for re lease.) During the first try, White missed the high note of the cadenza. The second time, she made two mistakes. Maestro Sodero encouraged her to try again. "But I was young enough not to be diplomatic," she recalls. "I told him I wasn't going to play that piece--I was tired from playing the Battle Hymn all morning long. Mr. Sodero warned me that it would cost the company double to bring in the orchestra for another session. But I told him, `If you have a session where you don't rehearse the Battle Hymn of the Republic, I'll play the piece!'" Her demand was met, and she recorded the piece the next day. The record sold so well that, when White picked up her paycheck, it was 50% more than she had expected to receive.

Violinist Rosalynd Davis also remembers that recordings often were made when the artists were exhausted from the hours spent achieving proper balances. As the Dann Trio, Davis, pianist Blanche Dann, and trumpet player Felice Dann traveled throughout the U.S. performing the famous Tone Test concerts, which were designed to win audiences over to the concept of the phonograph.

The concerts began with the trio playing along with one of its Edison recordings. Midway through the piece, the musicians would stop and the recording would continue. Newspaper accounts of such early live-vs. -recorded concerts reported that there was no difference between the sounds (which makes one wonder what future generations will think of our ears when they read of to day's similarly successful demonstrations). After several such A/B tests, the trio would give a regular performance.

Soprano Gladys Rice also participated in demonstrations. One of the most popular Edison stars, she drew large crowds with her evenings of com parison singing. The auditorium would be completely darkened so the audience would not know whether it was listening to her or to a recording and, therefore, would be able to judge the fidelity of the recording objectively.

Both Rice and baritone Douglas Stanbury re corded for Edison in the early Twenties--"When I was one and a half years old," Rice quips. Both re call two aspects of their Edison experience vividly. The first was the emphasis on technical perfection. The recording engineers would examine each wax master meticulously for evidence of crumbling, and the recording process would often have to begin all over again.

The second aspect was learning to use the recording horn to maximum advantage. The voice had to be projected exactly into the center to avoid excessive vibration and resulting distortion.

"Once the microphone came into the picture, the singer lost control and the engineer took over," Stanbury claims. "In those early days, we learned to work the horn in the way that was best for our own particular voices." "Working the horn" was almost athletic in some instances. Elizabeth Lennox recalls ducking down during orchestral introductions to allow the sound to enter the horn without being blocked by her body. Then she would take a deep breath and come up in dead-center position in front of the horn, just in time for her first note. That kind of timing reached its peak when Gladys Rice was called upon to sing a single high note for a famous opera singer who could not manage it. Somehow the two performed that feat without a collision.

In those post-World War I years, Edison exercised control not only over the technical standard of his recordings, but also over the repertoire.

Theoretically, two committees determined the latter. First, Edison, Stevens, and recording company vice president Arthur Walsh would decide which pieces were to be recorded and select the performers. After the masters were made at the New York studios, another committee of twenty Edison company officials was supposed to decide whether or not to release the record. According to Stevens, however, if the committee turned down a recording and Edison liked it, "he'd O.K. it. And if he didn't like the records, out they'd go, no matter if I said they were good or others said so." When other recording companies were having great success with "The Sheik of Araby," for example, Edison refused to have it recorded for the simple reason that he did not like the tune (his favorite song was "I'll Take You Home Again, Kathleen").

Edison was just as opinionated when evaluating performers. He would jot down his reactions to audition recordings; his cryptic notes would deter mine whether or not performers were invited to record for the Edison Phonograph Works. Some of those notes were saved by Clarence Ferguson, a cylinder -mold maker, and they are now part of the memorabilia of percussionist Lewis Green.

"She has too much tremolo for us. Also she drops her overtones in many places and becomes very sharp and thin." With these words, Edison dismissed Amelita Galli-Curci, the renowned soprano. His reaction to Claudia Muzio was not much different: "General voice fair. We do not believe we need her." Edison approved of Phil Baker, the singer and accordionist who in years to come would achieve fame as a radio quiz master: "Most perfect articulation. Think this man could do some good work." But Morton Downey received this evaluation:

"These type songs the public will not buy. There is no melody connected in sequence. The tenor's voice and interpretation is not such that it gives the song a chance even if it was melodious." Edi son decided that Rudolf Friml "won't sell. Friml is a pounder that dampens all his notes almost instantly. Every note is 50% fret noise and 50% music.

... If Friml has time, he might come over and I'll give him some pointers." Edison readily gave musical advice. He once asked Ernest Stevens to arrange a tune so that only intervals of a third or a sixth were used for harmony. (These were the intervals that did not grate on his ear.) He accepted Stevens' negative reply but added that there would be a man someday who would write a tune using only thirds and sixths.

Stevens did not often dare answer Edison in the negative. One day, when both of them were in the music room going over a new piece, someone came to the door to talk to the inventor. Stevens lost his place in the music completely but, since he had to keep playing until Edison accepted or rejected a tune, began to ,improvise. Five minutes later, Edison told him to take the music over to New York and record it with a symphony orchestra. "I had to do it or lose my job," Stevens declares. "When it came back, he listened to it and said it didn't sound anything like the way I played it, not at all. 'Those fellows over in New York don't know what they're doing,' he said, and then he threw out the record." On another day, Edison came into the music room to show his friend, Charlie Schwab, that his records were unbreakable. Stevens watched him take a record and drop it onto the floor, and "it broke into a million pieces. You never heard such language in all your life. He put his hands in his pockets and jumped up and down and yelled. He knew every cuss word in the English language!" As Edison's personal pianist, Stevens participated in numerous experiments. He particularly remembers the recording horn experiments of 1924. Edison had developed the theory that the optimum distance for sound to travel for acoustic recording purposes was 125 feet. To test this theory, he told the personnel at the Columbia Street laboratory to construct a solid brass recording horn 125 feet long, extending between two buildings and ending in the recording studio. The horn was made of brass sheets 1/16th of an inch thick, fastened with 30,000 rivets. The bell of the horn was seven feet in diameter; it tapered down to a tube 1 1/2 inches wide. Stevens was to play the piano in front of the immense horn.

"After all the initial trial recordings," he relates, "the old gent sent me to the icehouse and told me to have his men pack this horn-this 125-foot horn!--with ice. And then we'd go through the same experiments, and he'd listen to the results.

"That wasn't all. After that, he sent me to get a load of storage batteries and had the men pack the horn with them, and we'd go through the same experiments again. It was all experiment, right from the word `go.' They'd make a recording through the storage batteries in the horn, and he'd spend hours on it, to see he got it the way he wanted it." For another experiment, the walls and floor of the studio were completely covered with cow's hair; a canvas covered the layer of hair on the floor. Edison had the floor marked off into seventy five squares and then called in his pianist. "Ste vens," he said, "you get the saxophone player and put him on square No. 1 and have him play 'Lead Me with a Smile.' Have him go over all seventy five squares. I'll take a nap, and you call me when he's finished." So the saxophone player, and every other member of the orchestra, recorded on each of the squares. Edison listened to the recordings and selected the square that was best for each instrument. Between each trial recording, the inventor would take another nap.

"He said he slept four hours a day, but some times I think he was awake four hours a day. Yet in those four hours, he did more than you or I could do in a week," Stevens claims.

During those years at the Columbia Street laboratory, Edison also worked on a small amplifying horn to be attached to the body of the violin. It was one of many inventions that remained in the experimental stage. For himself, he also designed a special hearing horn that he used for listening to finished recordings. "But sometimes he'd get tired," remembers Stevens. "He'd get up and bite down on the rim of the piano to get the conduction through there, to feel the vibrations." By the time conductor Donald Voorhees met Edison late in 1926, the old gentleman had relinquished some of his control of the business. He was involved in a project for Ford and Firestone, investigating domestic sources of rubber. But the phonograph was his favorite invention, and he continued to sit in on recording sessions. While Voorhees recorded, Edison would slip into his little room off the studio and, at times, would doze off while listening.

"He was very nice, very intelligent, and very hard of hearing," recalls Voorhees. The conductor deeply admired Edison's insistence on fidelity of sound. There was very little experimentation during the late Twenties, but quality and, in particular, balance were still the focal points of the recording operation. Voorhees calls the results "the most faithful reproduction of the way the mu sic actually sounded. No distortion, amplification, or attempted so-called improvement would have been tolerated by him." Lewis Green also remembers the Edison of the late Twenties. His brothers, Joe and George Green, had begun recording for the Phonograph Works in 1916, and Lewis joined the Green Brothers Novelty Band in 1927. Shortly afterward, there was a reception for Edison artists at the Astor Hotel in New York City. The eighty-year-old Edison was surrounded by friends-among them Harvey Firestone--and, as usual, they spoke for him. Edison had always found it difficult to talk in public, and his high, raspy voice made him a poor speaker. But he still had a commanding presence, and Green re members that "everyone was in awe of him." Two years later, the Edison Phonograph Works ceased to exist. Edna White, who was on tour at the time, has always wondered why. "I guess everything happened all at once," she speculates.

"The Depression-vaudeville came to an end-all disasters seemed to be connected around that time. And in those last years, Mr. Edison was extremely busy with more important things than music." Radio came on the scene and for a while the record business declined everywhere.

Careers continued. Stevens started a music studio. Edna White organized her own band. Gladys Rice and Elizabeth Lennox became radio stars.

The Green Brothers Novelty Band made numerous records for several different labels. Donald Voorhees achieved fame with the Bell Telephone Hour.

But the days of the Edison studios were not entirely forgotten. Since 1974, the excitement of those years is recaptured annually in West Orange, New Jersey, when the Edison National Historic Site holds a reunion of the Edison stars. The old wax cylinders are played again, many of them one of the two original masters that were stored when the third was chosen for release. It is a time to praise the quality of those early recordings, a time of camaraderie and nostalgia. Stevens, now eighty-two years old and still teaching piano, feels a special sense of privilege: "I don't like to push myself forward, but I'm the last of those who really worked with Edison, and I'm proud and happy to have been associated with him. I always thought he was the world's greatest man."

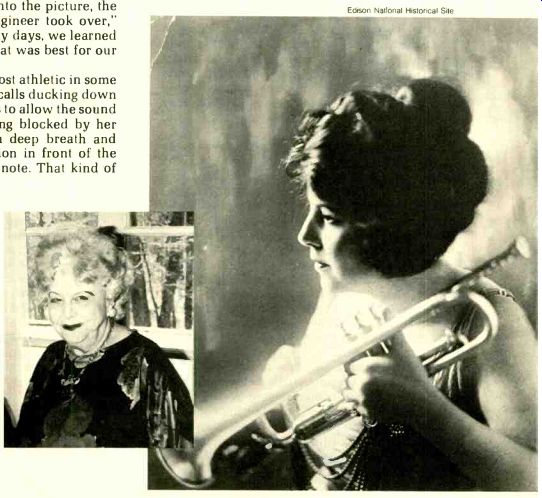

----- Edison National Historical Site: Edna White, whose

trumpet sound Edison judged "the loveliest .. . I ever heard," is

shown in a 1922 photograph and in one taken recently at her home in Greenfield,

Massachusetts.

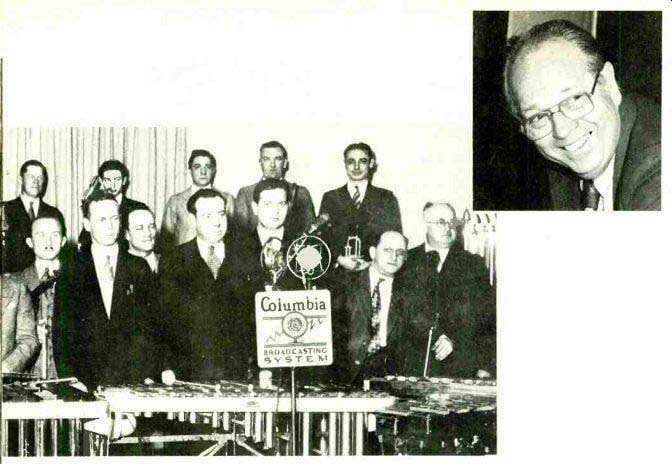

--------------- In the picture at above, taken during the late Twenties

when the Green Brothers Novelty Band was broadcasting for CBS, Lew is

directly behind the mikes, Joe to his right, and George to Joe's right

in the front row. By the time Lew (above, in his suburban Chicago home

recently) joined his brothers' band, their days of recording for Edison

were nearly over, but he recalls the inventor vividly.

-------------

(High Fidelity, Jan. 1977)

Also see:

The Parallel Careers of Edison and Bell; James A. Drake; Geniuses in sometime contact--and conflict

Link | --Link | --The Original Painting of Nipper; Oliver Berliner; His Master's Voice first came from a cylinder